Following S&P’s big downgrade of Eurozone sovereigns the markets said ‘so what?’ and pushed yields down, not up. Markets had already been pricing for downgrades, so the only real negative impact was on Portugal which fell out of some investment grade benchmarks. France and Austria now join the US in a new club of ‘not-quite AAA’ sovereigns. Altogether these three countries account for over 70% of AAA sovereign issuance, so even if another rating agency downgrades them where can investors go? It is more likely that benchmark-linked investors will simply change their criteria, and AA will become the new AAA.

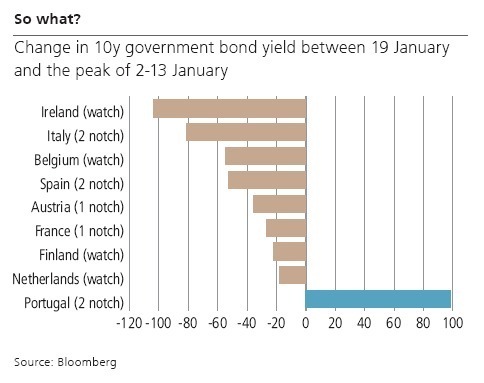

Announcements from rating agencies are a bit like a newspaper publishing the weekend football scores on a Monday – of no use to anyone who watched the games live. So when S&P announced their wave of downgrades on Friday the market pretty much said “so what?”. Government bond yields, with the exception of Portugal, actually fell after the announcement (see chart below).

Announcements from rating agencies are a bit like a newspaper publishing the weekend football scores on a Monday – of no use to anyone who watched the games live. So when S&P announced their wave of downgrades on Friday the market pretty much said “so what?”. Government bond yields, with the exception of Portugal, actually fell after the announcement (see chart below).

Portugal got the short straw because it had already been downgraded below investment grade by Moody’s back in July. With S&P joining Moody’s, Portugal falls out of the investment grade universe and out of a number of bond indices. Passive fund managers who benchmark against these indices are forced to sell, pushing yields up. The difference for the other sovereigns in the chart is that they didn’t fall out of any benchmarks yet – wait to see if the other rating agencies follow.

Bank ratings should usually suffer when the sovereigns that stand behind them are downgraded. So far S&P have not downgraded any banks, but they may be waiting to see if the new EU ‘bail-in’ legislation being proposed will change the relationship between banks and their sovereign governments. If sovereigns still bail out banks, then the bank cannot be better rated than the government. If sovereigns are no longer supporting banks to the same degree, then the risk of bank debt has gone up. Once again, markets know this is coming.

The downgrades of France and Austria also imperilled the rating of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which was duly downgraded to AA+. The EFSF is effectively a mechanism for better-rated countries to ‘lend’ their credit rating to worse-rated countries. As such, it is only as good as the credit ratings of those who pay in. The EFSF was designed for EUR 440 billion, but there are only enough AAA guarantees for just over half that amount (as far as S&P are concerned). Given that the EFSF has only raised about EUR 22 billion so far and is due to be replaced by the prefunded European Stabilisation Mechanism this summer, the downgrade is unlikely to have much impact.

Perhaps we are being a bit harsh on the ratings agencies by demanding too much of them. Both the markets and the ratings agencies got the sustainability of Eurozone periphery debt badly wrong over the last decade. Perhaps it is better to think of the rating as putting a seal of approval on market movements, essentially declaring that the new price level is more than just a temporary panic. On the other hand, after

six months of elevated French spreads over German bunds you would think most people would have already realised that risks had changed.

Losing a rating is easier than getting an upgrade. Many periphery countries, especially Italy, have instituted significant structural reforms to improve their outlook. It will be years before these have a clear effect, and even longer before they are recognised as having an effect. Until that time, the hopes of an upgrade are small.

The symbolic value of a rating change should not be underestimated – just ask French President Sarkozy after he next meets UK Prime Minister Cameron. Seeing France downgraded while Germany’s AAA rating was confirmed is also a public declaration of something that has been clear to many observers for some time. France is no longer the lead player or even equal lead player in European policy.

Welcome to the club

With their downgrades to AA+, France and Austria join the US in a new club of ‘not-quite AAA’ sovereigns. ‘Not quite’ because almost everyone requires two rating agencies to downgrade a sovereign before they consider it a full downgrade. Does this mean that France and Austria will now face higher borrowing costs? The US had yields around 3% in July, S&P downgraded them on 5th August and yields promptly fell to around 2% and are still around that level. So the answer from the US is a clear “no”.

It is actually fascinating that France and Austria have the same sovereign ratings as the US. Of the three, only the US has its own printing press. Would the US really default rather than just print more USD to meet their USD-denominated obligations? Monetising their debt would not formally count as a default, even if you took a big loss on the real value of the bond.

The US was not kicked out of any benchmarks by S&P’s downgrade, nor were France and Austria. S&P may have been brave to be the first to downgrade the US (and potentially incur the wrath of Congress) but the truly brave move would be if either Fitch or Moody’s downgraded the US, France or Austria. This would cost those countries their AAA status and lead to them being sold by ‘AAA-only’ funds. In all likelihood other countries with lower ratings are more likely to face a second rating downgrade first.

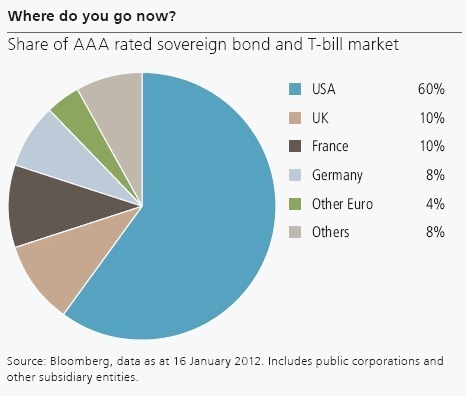

This begs the question of where a ‘AAA-only’ investor should go. The US alone accounts for about 60% of this market, and France accounts for a further 10% (see chart below). France also accounts for almost half of the EUR-denominated AAA sovereign assets. Investors could either sell or simply acknowledge that they will have to reduce their criteria slightly. AA would become the new AAA.

Bank ratings should usually suffer when the sovereigns that stand behind them are downgraded. So far S&P have not downgraded any banks, but they may be waiting to see if the new EU ‘bail-in’ legislation being proposed will change the relationship between banks and their sovereign governments. If sovereigns still bail out banks, then the bank cannot be better rated than the government. If sovereigns are no longer supporting banks to the same degree, then the risk of bank debt has gone up. Once again, markets know this is coming.

The downgrades of France and Austria also imperilled the rating of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which was duly downgraded to AA+. The EFSF is effectively a mechanism for better-rated countries to ‘lend’ their credit rating to worse-rated countries. As such, it is only as good as the credit ratings of those who pay in. The EFSF was designed for EUR 440 billion, but there are only enough AAA guarantees for just over half that amount (as far as S&P are concerned). Given that the EFSF has only raised about EUR 22 billion so far and is due to be replaced by the prefunded European Stabilisation Mechanism this summer, the downgrade is unlikely to have much impact.

Perhaps we are being a bit harsh on the ratings agencies by demanding too much of them. Both the markets and the ratings agencies got the sustainability of Eurozone periphery debt badly wrong over the last decade. Perhaps it is better to think of the rating as putting a seal of approval on market movements, essentially declaring that the new price level is more than just a temporary panic. On the other hand, after

six months of elevated French spreads over German bunds you would think most people would have already realised that risks had changed.

Losing a rating is easier than getting an upgrade. Many periphery countries, especially Italy, have instituted significant structural reforms to improve their outlook. It will be years before these have a clear effect, and even longer before they are recognised as having an effect. Until that time, the hopes of an upgrade are small.

The symbolic value of a rating change should not be underestimated – just ask French President Sarkozy after he next meets UK Prime Minister Cameron. Seeing France downgraded while Germany’s AAA rating was confirmed is also a public declaration of something that has been clear to many observers for some time. France is no longer the lead player or even equal lead player in European policy.

Welcome to the club

With their downgrades to AA+, France and Austria join the US in a new club of ‘not-quite AAA’ sovereigns. ‘Not quite’ because almost everyone requires two rating agencies to downgrade a sovereign before they consider it a full downgrade. Does this mean that France and Austria will now face higher borrowing costs? The US had yields around 3% in July, S&P downgraded them on 5th August and yields promptly fell to around 2% and are still around that level. So the answer from the US is a clear “no”.

It is actually fascinating that France and Austria have the same sovereign ratings as the US. Of the three, only the US has its own printing press. Would the US really default rather than just print more USD to meet their USD-denominated obligations? Monetising their debt would not formally count as a default, even if you took a big loss on the real value of the bond.

The US was not kicked out of any benchmarks by S&P’s downgrade, nor were France and Austria. S&P may have been brave to be the first to downgrade the US (and potentially incur the wrath of Congress) but the truly brave move would be if either Fitch or Moody’s downgraded the US, France or Austria. This would cost those countries their AAA status and lead to them being sold by ‘AAA-only’ funds. In all likelihood other countries with lower ratings are more likely to face a second rating downgrade first.

This begs the question of where a ‘AAA-only’ investor should go. The US alone accounts for about 60% of this market, and France accounts for a further 10% (see chart below). France also accounts for almost half of the EUR-denominated AAA sovereign assets. Investors could either sell or simply acknowledge that they will have to reduce their criteria slightly. AA would become the new AAA.

The world as Germany’s Germany?

On a related note, earlier this week the IMF announced that they would need more contributions from their members if they were to contain the Eurozone crisis. In response, the US and Canada pointed out that Europe has enough resources to deal with its own problems, if only Germany and the core open up their wallets. Germany tells Greece to face pain rather than expect a bailout. The rest of the world is now telling Germany to accept some pain rather than expect a bailout.

The IMF may need more funding, but most members would like to see this as insurance to help other countries from the fallout of a Eurozone collapse, not as a bailout fund for Europe.

Joshua McCallum - Senior Fixed Income Economist - UBS Global Asset Management

Gianluca Moretti - Fixed Income Economist - UBS Global Asset Management

www.ubs.com

The views expressed are as of January 2012 and are a general guide to the views of UBS Global Asset Management. This document does not replace portfolio and fund-specific materials. Commentary is at a macro or strategy level and is not with reference to any registered or other mutual fund. This document is intended for limited distribution to the clients and associates of UBS Global Asset Management. Use or distribution by any other person is prohibited. Copying any part of this publication without the written permission of UBS Global Asset Management is prohibited. Care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of its content but no responsibility is accepted for any errors or omissions herein. Please note that past performance is not a guide to the future. Potential for profit is accompanied by the possibility of loss. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the original amount invested. This document is a marketing communication. Any market or investment views expressed are not intended to be investment research. The document has not been prepared in line with the requirements of any jurisdiction designed to promote the independence of investment research and is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research. The information contained in this document does not constitute a distribution, nor should it be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security or fund. The information and opinions contained in this document have been compiled or arrived at based upon information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and in good faith. All such information and opinions are subject to change without notice. A number of the comments in this document are based on current expectations and are considered “forward-looking statements”. Actual future results, however, may prove to be different from expectations. The opinions expressed are a reflection of UBS Global Asset Management’s best judgment at the time this document is compiled and any obligation to update or alter forward-looking statements as a result of new information, future events, or otherwise is disclaimed. Furthermore, these views are not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, asset class, markets generally, nor are they intended to predict the future performance of any UBS Global Asset Management account, portfolio or fund.

© UBS 2012. The key symbol and UBS are among the registered and unregistered trademarks of UBS. All rights reserved.

On a related note, earlier this week the IMF announced that they would need more contributions from their members if they were to contain the Eurozone crisis. In response, the US and Canada pointed out that Europe has enough resources to deal with its own problems, if only Germany and the core open up their wallets. Germany tells Greece to face pain rather than expect a bailout. The rest of the world is now telling Germany to accept some pain rather than expect a bailout.

The IMF may need more funding, but most members would like to see this as insurance to help other countries from the fallout of a Eurozone collapse, not as a bailout fund for Europe.

Joshua McCallum - Senior Fixed Income Economist - UBS Global Asset Management

Gianluca Moretti - Fixed Income Economist - UBS Global Asset Management

www.ubs.com

The views expressed are as of January 2012 and are a general guide to the views of UBS Global Asset Management. This document does not replace portfolio and fund-specific materials. Commentary is at a macro or strategy level and is not with reference to any registered or other mutual fund. This document is intended for limited distribution to the clients and associates of UBS Global Asset Management. Use or distribution by any other person is prohibited. Copying any part of this publication without the written permission of UBS Global Asset Management is prohibited. Care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of its content but no responsibility is accepted for any errors or omissions herein. Please note that past performance is not a guide to the future. Potential for profit is accompanied by the possibility of loss. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the original amount invested. This document is a marketing communication. Any market or investment views expressed are not intended to be investment research. The document has not been prepared in line with the requirements of any jurisdiction designed to promote the independence of investment research and is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research. The information contained in this document does not constitute a distribution, nor should it be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security or fund. The information and opinions contained in this document have been compiled or arrived at based upon information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and in good faith. All such information and opinions are subject to change without notice. A number of the comments in this document are based on current expectations and are considered “forward-looking statements”. Actual future results, however, may prove to be different from expectations. The opinions expressed are a reflection of UBS Global Asset Management’s best judgment at the time this document is compiled and any obligation to update or alter forward-looking statements as a result of new information, future events, or otherwise is disclaimed. Furthermore, these views are not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, asset class, markets generally, nor are they intended to predict the future performance of any UBS Global Asset Management account, portfolio or fund.

© UBS 2012. The key symbol and UBS are among the registered and unregistered trademarks of UBS. All rights reserved.